Published: 31.1.2022.

The article was edited and published by Andrea Božić

After several cholera epidemics, the city of Berlin was the last European capital to get running water.

Paris had a centralized water supply system, as did Vienna and of course London. The renowned Roman aqueducts had been supplying Roman settlements with water more than 2,000 years ago. According to the census from December 3, 1849, Berlin had exactly 423,902 inhabitants, 5,600 wells - and a cholera outbreak.

The city suffered 13 epidemics between 1831 and 1873; diarrhea was suspected to be transmitted by miasms (vapours). The cause was unknown, but was thought to come from the east, as implied by the name the "Asian Hydra". From September 1831 to February 1832 alone, 1,426 people died of cholera in the Prussian capital. Despite warnings that the epidemic could have something to do with water, the short-sighted, frugal judge refused to take precautionary measures. Although industrialization and a massive influx of new workers gained new momentum around 1840, it was not until 1852 that Berlin became the last European capital to start building a water supply system.

Safety through hygiene

The driving force behind the project was police commissioner Karl Ludwig Friedrich von Hinckeldey - one of the most interesting figures for those wanting to understand the Prussian state in the era following the failed democratic revolution of 1848-49. On the one hand, Hinkeldey took repressive action against subversives, on the other he sought to alleviate social concerns which he recognized as a danger to the monarchy: he established a professional fire brigade, reorganized the city’s sanitary service, constructed baths – and ensured the construction of the water supply system.

In 1848, Hinckeldey recommended the construction of an aqueduct from lakes Wandlitz and Liepnitz to Berlin. The answer was vague: "but we can only take part in it to the extent that it does not cost us anything." The police commissioner, the scope of whose authority had been expanded with the new city constitution and municipal codex in 1850, finally managed to convince the minister of commerce, the minister of the interior and the city of Berlin. King Friedrich Wilhelm IV did not need persuasion - he supported the project from conviction.

However, there were no suitable construction companies in Prussia. On December 11, 1852, Hinkeldey signed a contract with English contractors Sir Charles Fox and Mr. Thomas Rushell Crampton, who agreed to build canals to "streets, alleys and squares" using state-of-the-art methods. The estimated cost was 1,500,000 thalers. The construction was to begin in 1853 and be completed by July 1, 1856. The contract was concluded for a 25-year period. The king added clauses to the contract stating, for example, that the city government has no vote in the matter, that the profits of British entrepreneurs may not exceed 15 per cent, and in return the Prussian government granted them "special protection in all matters".

Berlin Water Works, London

The Berlin Water Works Company was founded in London. The Berlin gas factory was also in English hands at the time - owing to the British technological leadership. Berlin’s mayor, Heinrich Wilhelm Krausnick, still maintained that cholera had nothing to do with water. After all, cholera has been raging even worse in other cities. In the light of our current experience with the corona pandemic, the nearly 200-year-old reports of infections, hotspots, fear and helplessness sound frighteningly familiar. In 1831, the first death from cholera was boat related. It was a commuter who docked at Charlottenburg with his peat barge. Only a day later, the area around Schiffbauerdam, where many barges docked at the time, was affected. Just a few days later, the temporary cholera hospital reported to be overcrowded.

Fencing Berlin off did not help. Ambulances and hearses rolled through the streets, ringing to announce their arrival. Berliners were not impressed. They would say things like: “Just don’t make it creepy,” drink preventive brandy and have fun as usual. The theaters remained open. Only the king, still Friedrich Wilhelm III at the time, temporarily withdrew to Charlottenburg, worried.

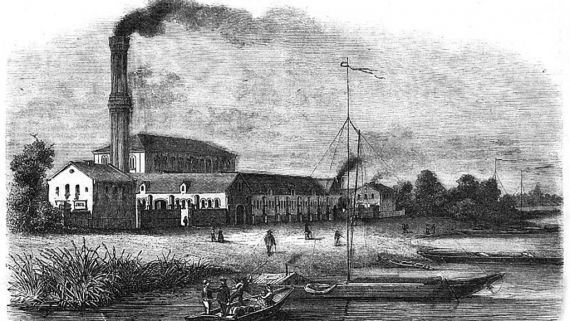

Water supply system in Stralauer Tor

In immigrant neighborhoods, and especially in the Neu-Voigtland slum (later Rosenthaler Vorstadt in what would become the Mitte), the number of cholera sufferers rose sharply in the cramped housing with medieval hygienic conditions. University professor Friedrich Hufeland wrote in shock: “It is certainly a disgrace for us Berlin doctors that since cholera has become prevalent in civilized countries, i.e. where medical police has been instituted and registers of death exist, nowhere have so many people died from it in proportion to the number of patients as here."

In 1853, the first stone of the first Berlin aqueduct was finally laid in the vicinity of the Stralauer Tor (nearby today's Oberbaumbrücke). It is hard to believe that the English began work on July 1, 1856, just as agreed in the contract. Little by little, buildings were connected to the water supply system - 314 after a year, 1,141 after three years. In 1859, Berlin Water Works realized its first profit and in 1868 the company disbursed dividends exceeding nine percent. A year later, the project stagnated. Expansion talks failed.

Meanwhile, the issue of wastewater removal was being increasingly raised. A sewer system was needed, but the first plan of the Prussian engineer Eduard Wiebe for such a system divised in 1861 met with direct opposition. Wiebe wanted to channel sewage underground through Berlin and finally into the Spree in the vicinity of today's Beusselstraße in Alt-Moabit. Various citizen initiatives were organized, pamphlets printed, petitions sent to government offices, and newspaper ads published. Resistance dragged on for over 10 years, delaying the all-important project as the city’s population exploded.

The first sewer

The objections revealed different interests: the construction of an underground sewer was too expensive for the city; the carriers did not want to lose the business of collecting toilet buckets every night; toilet bucket carriers, mostly poor women, feared for their earnings; the idea of demolishing entire streets to lay sewer pipes was frightening; the surrounding communities were worried that Berlin’s excrement would leak into their fields and so on.

Nevertheless, the population continued to grow. Berlin now wanted to implement a large-scale urban expansion plan, drawn up by the city’s chief architect James Hobrecht. The city terminated the restrictive contract with the London Water Works on 31 December 1873 and bought the company, resulting in the first communalization of the Berlin waterworks.

Meanwhile, cholera struck Berlin again in 1866. A commission led by Dr. Rudolf Virchow, head of the Berlin Hygiene Movement, was finally able to begin planning an underground sewer system. In 1849, Virchow estimated the life expectancy of the wealthy Berliners at 50 and poorer at 32. Cholera became a major motive for preventing infection from spreading through drinking water supplies and sewage.

In 1873, the construction of 12 wastewater drainage "radial systems" began. Within four years, the first 80 km were laid down and 2,415 buildings connected. The last segment of the radial system was put into operation in 1893, and the suburbs were gradually connected. The project, executed by James Hobrecht, was expensive; in fact, Berlin issued its first municipal bond to pay for the sewer system. But the network still works well today. Berlin has gained the reputation of one of the cleanest cities in Europe.

After that, the city was spared new cholera epidemics. When Berlin scientist Robert Koch identified the vibrio cholerae bacterium in Egypt in 1883 - which the Italian Filippo Pacini had already done in 1854 - he also proved that it was transmitted by water, which marked a breakthrough. In May 1884, Berlin triumphantly welcomed Koch - the world was able to overcome the horrors of cholera. It seems that we are not much better prepared for new epidemics today than Berlin was 200 hundred years ago, the author of the text, Maurice Frank, concludes.

Prepared by: Astrid Werbolle

Source: Berliner Zeitung

Find out more at:

https://www.google.com/url?sa=i&url=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.berliner-zeitung.de%2Fen%2Fwhy-the-english-built-berlins-first-waterworks-li.149349&psig=AOvVaw1bWyCphxNET9P87Rc1CvFF&ust=1643453703110000&source=images&cd=vfe&ved=0CAwQjhxqFwoTCPjNvKCk1PUCFQAAAAAdAAAAABAZ